Zeno’s Paradoxes crop up occasionally. There are several paradoxes labelled as Zeno’s. Two of these are: Achilles and the Tortoise, and, the dichotomy paradox (or the race course paradox)

These are all basically the same sort of problem, about breaking down motion into an infinite series of ever smaller steps.

The runner of a race goes like this:

A runner starts running the length of a race track. At the half-way point he has covered half the distance, with half remaining. When he gets to half the remaining distance he still has the other half of that second distance remaining. At each ever shorter half-way point he has covered half the distance remaining, but always has half the distance to complete. This continues, with next half-distance remaining, indefinitely. He never completes the race. But, we know runners do finish races. This is supposed to be a paradox – two ‘truths’ that are incompatible:

- The runner never completes the race ‘theoretically’, because he forever only completes ever smaller half distances.

- The runner does complete the race, because we see him complete it.

The problem is with the first ‘theoretical’ presentation.

What’s actually happening, with the runner of a race, is we tend to assume him to be traveling at a constant speed S, and yet the never ending half distances make it appear that he never completes the race. Paradoxical? Only if you think of a normal runner at constant speed, while thinking of this runner with each half length taking the same time.

Constant Speed

Supposing that we look at his position, x, at times, t, and X is the length of the track:

x0, x1, x2, x3, …, xn, x(n+1), …

t0, t1, t2, t3, …, tn, t(n+1), …

The difference between each is:

dxn = x(n+1) – xn: dx0 = x1 – x0, dx1 = x2 – x1, …

dtn = t(n+1) – tn: dt0 = t1 – t0, dt1 = t2 – t1, …

The paradox tells you that dx is being halved each time, but may neglect to tell you that if the runner is moving at constant speed then dt is also being halved each time:

dx1 = dx0/2, dx2 = dx1/2, …

dt1 = dt0/2, dt2 = dt1/2, …

The time intervals are halving too.

So, the speed is still constant: dxn/dtn = S, period to period.

Constant Time Intervals – Reducing Speed

The other view of the paradox, the one presented when looking at the detail, thinking only about the distances, leaves you with this impression:

dx1 = dx0/2, dx2 = dx1/2, …, dx(n+1) = dxn/2

dt1 = T, dt2 = T, … where T is constant. If the paradox is expressed with the intention of declaring a never ending race then this will be stated explicitly.

So, s the speed is halving each step:

sn = dxn/T = dx(n-1)/2T = s(n-1)/2

which would take infinite time to complete.

So, what you think you’ve got is a half-life-like expression: where the distance is asymptotic to the end point and never actually reaching it, in principle:

Stopping Time, or Never Ending?

Once the constant speed distance intervals become smaller than a part of the runner’s foot, and the time intervals become smaller than we can detect, he seems to become stationary. You’ve stopped time – it’s as if the runner can never complete the race. But of course you are supposedly looking at the runner in real time (in your mind’s eye), while being able to see these ever smaller distances and times, as if you see him stop. But in reality, at constant speed, these smaller intervals flash by in real small times and we do see the runner complete the race.

With the constant time intervals the runner actually runs slower and slower in real-time. Again he appears to become stationary because each interval (let’s say T = 1s) his distances are really getting smaller and smaller each second. Asymptotically, in principle, he never reaches the end – or, more specifically, the total time (the sum of all the T’s), extends indefinitely with the number of intervals. He would have to run so slow as he approaches the end that he would again appear to freeze.

Finite sum of a convergent infinite series

Another way of looking at the (correct) constant speed scenario is by summing intervals.

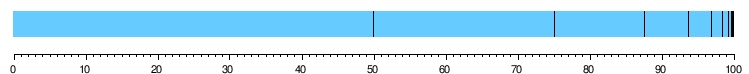

Assume the total distance is 100m, and the time taken to travel the distance is 100s. The speed S is:

S = 100m/100s = 1m/s (Ok, so he’s 10 times slower than Carl Lewis on his first 10s 100m)

Normalised to unitless 1 (i.e. 100m = 1 and 100s = 1) this becomes:

S = 1/1 = 1

The paradox states each distance interval is halved, and in total you have a finite sum from an infinite series:

1 = 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + …

The same must apply for the time intervals:

1 = 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + …

So, again, the speed is 1/1 = 1.

If Ttot is the time to complete the race: Ttot = S/X

Then half the distance at constant speed: Th = Ttot/2

The series view is then:

Ttot = Th + Th/2 + Th/3 + …

Ttot = Th + Th(1/2 + 1/3 + …) = 2Th

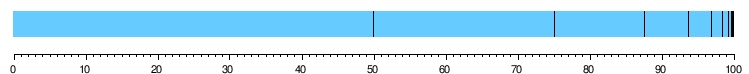

Infinite sum of a divergent infinite series

For the constant time interval we have a divergent series:

So, the times at each x are:

x0, x1, x2, …

0, T, 2T, …

or

Ttot = T + 2T + 3T + … -> infinity

For a more detailed look at the maths of all this try these pages from S. Marc Cohen at Washington.

Conclusion

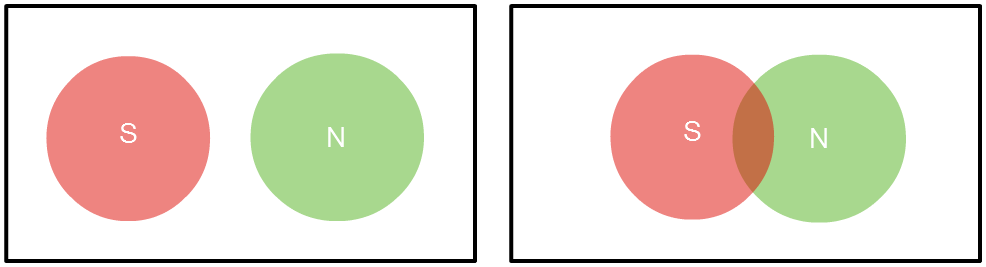

What we are led to believe is that we have a paradox concerning a single type of motion, with contradictory results. But it is simply two definitions of the motion of travel, neither of which is explicit in the statement of the paradox, and neither of which is problematic in isolation.

Some formulations may state explicitly that the time intervals are constant – in which case there is only one single description of motion, and you just have to avoid the trap of having the motion of a constant speed runner in the back of your mind to avoid coming over all paradoxical.

So, it’s not a real paradox:

“a statement or proposition that seems self-contradictory or absurd but in reality expresses a possible truth.”

The ‘paradox’ contains two actual truths masquerading as a self-contradictory single truth, or a single truth that you have mistaken for two. You have been conned.

Getting Real

Constant speed

We could object that it takes time to accelerate at the start of a race (even at 10m/s), but the example here just simplifies the case of a variable speed natural runner. You could change the definition of the race, so he accelerates to 10m/2 before x0, and decelerates after passing X.

Constant Time Periods

The constant time interval is even more unrealistic. There is a difficulty with infinitesimal distances, even in the case of the constant time intervals. The atom on the tip of the runner’s nose is sufficiently large to jiggle back and forth across the finish line as the runner is halving his speed on approach to the finish. And good luck with dealing with this as you approach the Planck length.

Half Life:

In practice the half life of a piece of caesium isn’t infinite. A mole of caesium contains 6.022 × 10^23 atoms – which is a finite number, so it would eventually decay to zero.

But, it is a thought experiment after all, and philosophers, even back in Zeno’s time, weren’t too hot on thinking through thought experiments. Don’t get me started on ‘the heap‘.