I wanted to give an example of religious wooly thinking, and here’s one. You can watch the video here (h/t Lesley), and you might want to do that first to get the flavour of it. Or, you could read this first, and then go back and listen with some of these questions in mind. By the time you read this the full video may have been taken down, so here I’m working on the part-transcript I took while it was up.

This piss-take video gets right to the point (h/t Lesley again).

Rob starts off criticising what he sees as obviously ridiculous ‘signs’, as if he’s the rational one, appealing to you too as rational Christians, not prepared to believe what are clearly nonsensical claims. This is the psychological technique of inclusion whereby he invites you into his circle of knowing believers that aren’t fooled by false claims of miracles and prayer. Little pauses and glances aside for dramatic effect always add to the performance – and Rob is a performer. Is it me, because I don’t get it, or does he come across as really insincere to you?

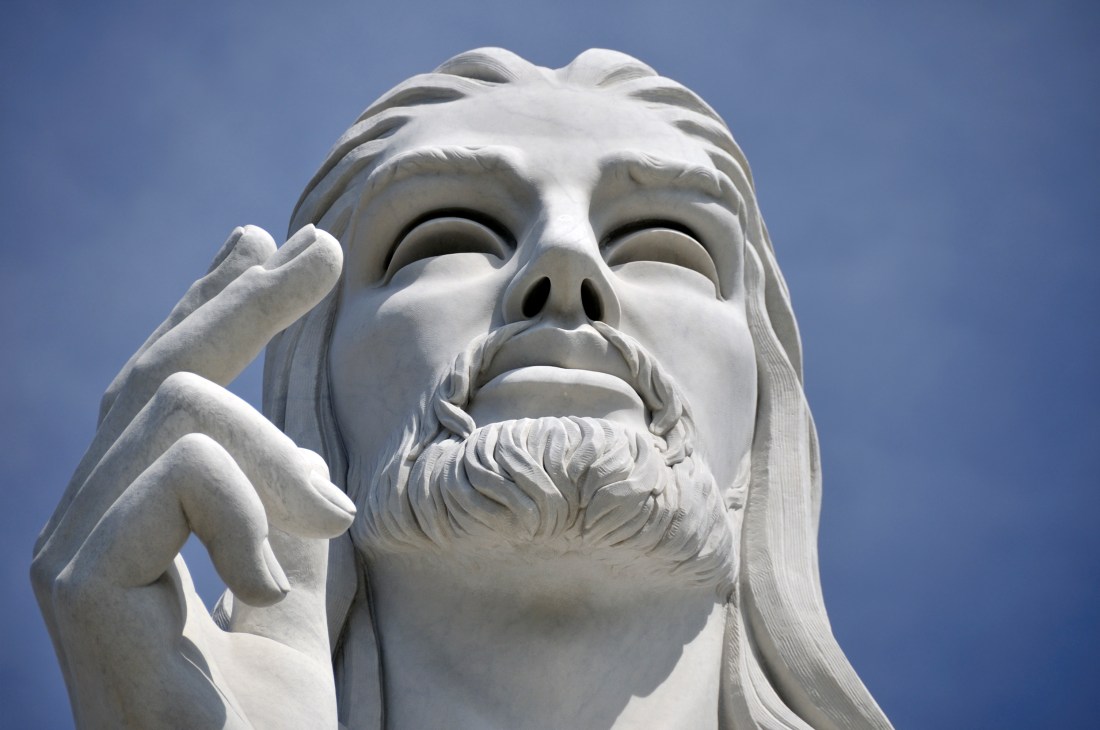

“…old man…long white beard…” – He’s setting up his own straw man to show how he can knock it down.

But from here on in, it gets really woolly. So much so that it’s hard to critique in it’s entirety. It’s hard to pick out any meaningful idea to criticise because the way it’s presented is in a dreamy hypnotic style that drifts in and out of sense. There’s nothing for it but to dive right in and comment as it goes. From here on the words are Rob’s – my comments are italicised in square brackets – I’m going to have a quiet word with Rob, by interjecting in his consciousness, just as God does. I’m not entirely sure if this will work.

Rob continues with his observations on and criticisms of an existent God…

“..concept of God is a God who is outside of everything; a God who is essentially somewhere else. A God who made the world and who then stands back, and then, like, watches it from this other vantage point. A God who’s there [Pointing dramatically helps, Rob?] and then from time to time comes, here [Overdid the theatrical pause there Rob – looked a little fake (but this is quite muted compared to your Resurrection video)]. But the problem with this concept of God is you end up you haven’t even proved that this God even exists [That’s right, you haven’t; and nor do you ever prove, or give evidence for, or even a rational reason to accept, any of the bullshit that you invent to replace this God]. And so what happens is we start with real life, we start with existence, this, what we all agree actually exists [This is a good start]. And then people end up arguing and debating and discussing whether there’s a God somewhere else who has something to do with this [Well, some Christians will persist in believing God exists as an entity, and some will come back to it some time after denying it. But note what’s really happened here, Rob. You’ve managed to distance yourself from any requirement to define an existent God, without actually denying that God actually exists – which comes in handy later when you allude to God’s existence by saying what God ‘is’ or what God ‘is like’, or when you talk about why we were created, by God. Rob, I accuse you of woolly thinking, but really it’s quite an astute move – you been reading up on hypnosis techniques on how to confuse the listener?].

But the writers of the Bible seem far less interested in proving whether God exists, and far more interested in talking about what God is like. [How would you expect to find out what something is like when you’re not even sure it exists – or do you really think God exists, but you just choose to skip that bit because it’s an inconvenient problem? So, Rob, have we forgotten Genesis then, God as creator; you’re sure?] Like in the book of Exodus, a man named Moses wants to know God’s name and God responds “I am”[‘I am’, as in I exist? Confused Moses? You will be.], and then later God reminds Moses that when Moses heard God’s voice he saw no shape or form [Moses wouldn’t see God if Moses was hearing voices. When people ‘hear voices’ it’s real. Though the ear isn’t receiving any sound the auditory cortex is actually active, just as if they were really hearing a voice. So, we’ve established that the religious are hearing things. But, if God doesn’t exist, what is it that’s actually speaking to Moses? Couldn’t be Moses’s own sub-conscious could it? No, that’s way too straight forward for a Biblical story; heaven forbid – and apparently it does forbid the bleedin’ obvious. But, let’s continue Rob.]

God is beyond anything our minds can comprehend [But, Rob, theists are still keen to tell us God is love, etc., as you do later. So let’s keep this incomprehensibility in mind for when you get round to comprehending him, which is what you do when you describe him.] What does it mean to have a personal relationship with this kind of God? [Good question, let’s see how it goes.] That’s, like, hard to get your mind around [Well, it would be, Rob, since you haven’t told me anything yet, except there’s a non-existent God, or a God that exists but you don’t want to get into that, or a God who’s beyond comprehension – it is a tall order when you don’t appear to know what it is you’re talking about. Could it possibly be you’re inventing a relationship with yourself as a duality, as if there are two Robs, or is this friend completely imaginary?]

But you know I believe that God listens and God cares and God’s involved [Why? Given what you’ve just said, Rob, this statement is right out of the blue. Here’s an idea, why don’t we give this ‘out of the blue’ unsubstantiated belief that doesn’t rely on any reason whatsoever, why don’t we give it a name, like…’faith’ – oh, you already have? OK.], but I find the whole relationship idea hard to comprehend [You should, Rob! And you should be asking yourself serious sceptical questions, not trying to affirm it, not trying to use flaky pshyce techniques to influence your audience into falling for it too. But, so far, all you’ve said is you believe that God does a few things. But why do you believe that?]

And then, loving this kind of God [Whoa! What kind? You haven’t been able to comprehend him to say what kind he is.], what does that look like [You mean what does love look like, what does a relationship with a non-entity look like? What are you really asking Rob?], what does it mean [That’s a better question. No answer due any time soon.], and … how do you do it? [Another good one. No Answer coming.] Well when I think of God I hear a song [Nutty attempt coming up, but no real answer. This is semantically okay, but meaningless, unless you take it literally, that when he thinks of God he does actually hear a song. But, let’s take it that you’re about to use the act of listening to a song as a metaphor for constructing a relationship with God, or of hearing God. Doesn’t seem like a great metaphor to me – there’s supposed to some way of tallying the metaphor to the target, but this seems a little flaky. But, I forget; the whole point of this babble is to cuase confusion in the mind of the listener; sorry Rob. ].

It’s a song that moves me, it has a melody and it has a groove. It has a certain rhythm. [So, it’s a relationship that moves you? Is the metaphor really necessary for this bit? I would expect any good relationship to be like this, so the metaphor isn’t really meeting it’s objective, which is to explain a relationship with an incomprehensible being.] And people have heard this song for thousands and thousands of years across continents and cultures and time periods. [All Christians, or other theists too? And is the song we’re hearing now God, or is he saying many people have had relationships with God, which seems like a song? Confusing.] People have heard the song and they have found it captivating [So far this is song as a metaphor, not for God, but just what it feels like to those who have a relationship with God – they’ve had a captivating experience – okay, but again, this could be any relationship, not one specifically with an incomprehensible entity.] and they’ve wanted to hear more [okay, they are hooked on the song, but really they are hooked on the experience of the relationship. Got that].

But there have always been people who say there is no song and have denied the music, but the song keeps playing [Why don’t you just say there have always been atheists, or if that implies too much non-existence that you don’t want to get into then just say non-believers. The metaphor isn’t doing much work – but you’ve started it Rob, so you’re stuck with it I guess. But, yes, we atheists say your ‘song’ is only in the heads of those having the delusion]. And so, Jesus came to show us how to live in tune with the song [How to remain deluded? How to continue to fool yourself? How to convince yourself that the song inside your head is real in some sense, or that the relationship you have constructed is a real relationship with something real (yet incomprehensible) and not just like a relationship with a child’s imaginary friend?] ..way and the truth and the life [What does this mean? These are favourite meaningless tropes, rhetorical devices use for hypnotic effect. They are nonsense].

This isn’t a statement about one religion being better than all the others. The last thing Jesus came to do was start a new religion [Oops! What have those damn Christians gone and done? But, good point. How does that work with religions, Rob? A Jewish man comes along with some neat ideas, but not wanting to start a new religion, but inadvertently does, based on him (through no fault of his own). Would he reject Christians as idolaters?] he came to show us reality at its most raw [What? In what way did he do this, and what does it mean anyway? Was he explaining evolution red in tooth and claw? Don’t think so. And what has that to do with the song as metaphor for relationship with God? Don’t forget the song Rob.], and came to show us how things are [We didn’t know already? What did he actually show us? He had some nice cultural ideas, which were great, but that’s about it. Is this meant as in the hippy ‘tell it like is man’ phrase, was Jesus merely a hippy?] Jesus is like God [But we don’t know what the incomprehensible God is like yet, so what’s the point of saying Jesus is like him, unless Jesus is incomprehensible too?], and in taking on flesh and blood [Thought Jesus was God? He was like God in taking on flesh and blood? But God only took on flesh and blood in Jesus? Confusing meaningless hypnotic rhetoric], and so in his generosity and in his compassion, that’s what God’s like, in his telling of the truth, that’s what God’s like, in his love and forgiveness and sacrifice, that’s what God’s like [So, now we are defining God, through Jesus, as a simile? Hold on. I thought God was incomprehensible. Or is this another metaphor, Jesus’s behaviour as metaphor for God? The only incomprehensibility here is you Rob] That’s who God is, that’s how the song goes. [Utter bullshit. This has turned into a definition of God – remember the incomprehensible God that can’t be explained? And I thought this song was about one’s relationship with God, not a declaration of what this non-existent incomprehensible entity is].

[Something I’ve noticed here Rob, is how the sentences aren’t always complete, how the subject switches subtly from what is, at one moment, clearly a concept, to later being assumed to be fact. Admire your grasp of hypnosis Rob Oops, hold on, you’re back to the song.]

The song is playing all around us all the time [Just in your head, Rob, but you can’t tell the difference] the song is playing everywhere [No it isn’t Rob. Honestly. Unless you mean everywhere to you – which it would if it’s constantly playing in your head]. It’s written on our hearts [you mean you really feel the experience that you have just self-induced. Fair enough]. And everybody is playing the song [I thought we were listening to it, just hearing it, but now we’re playing it too. But, no we’re not Rob. Honest. I don’t know who’s supposed to be the most confused, Rob, you or the listener (I mean listener to you Rob, not listener to the song – sorry, I’m just confusing you/me/them all the more).].

See, the question isn’t whether or not you are playing the song [You just said we were! but now that’s not significant?], the question is are you in tune? [So, are we all playing, but some not in tune, or are some not actually playing the song but only hearing, in which case how can they get in tune if they aren’t actually playing?].

Like it’s written in the book of Acts …God gives us life and breath and everything else. God is generous [which is easy for a non-existent entity who relies on the faithful to not only to invent Him, but to invent his generosity]. So when I’m, like, selfish and stingy and I refuse to give, I’m essentially out of tune with the song. Later, in one of John’s letters he says that God is love; unrestrained, unconditional love [Another definition of that which is beyond comprehension – so you learned this trick from John?] So when you see somebody sacrifice themselves for another, for the wellbeing of somebody else, it’s like they’re playing in the right key, that’s why it’s so inspiring and powerful; they’re in tune with the song [Not just in tune, but also in the right key, ok. In tune with the person they are helping or in tune with God or in tune with the relationship with God? And suddenly sacrifice is related to the tune – I thought the tune was about a relationship, with God. Well, if any of your audience are having trouble keeping up with this, then good, they’re supposed to, right Rob?]

Now some people know all sorts of stuff about music, and they’ll talk about pitch, and modes, and keys [yes, you just did] and instruments, so they can hear things that maybe other people don’t, they can hear subtlety and nuance in the song, they appreciate things other people might miss, but it’s also possible to be so caught up in the technical aspects of the song that you miss the simple pure enjoyment of the song. [It’s also possible to be so caught up in the bullshit of presenting the message that there ends up being no discernible message – you might be stretching it a bit here Rob.] And there are people who talk as if they know everything about being a Christian, and yet they can seem way out of tune[Nice one Rob, distancing yourself from those Christians that claim to know, without acknowledging that through this message you are sort of claiming to know yourself. You are so slick]. And there are others who would say they don’t know much at all about the Christian faith, and yet they can see very in tune with the song[i.e. you Rob? – Say it Rob, don’t be bashful. Okay, so this snippet is just using the same ongoing metaphor, but this time to conjure up how some people may be interpreting scripture wrong, or God wrong? It’s so confusing it’s difficult to determine what the real point is. Does it make the audience feel in-group or out-group? If they’re in already they feel warm and cosy, if they’re out they’re missing out and want to get in? More rhetorical psyche trickery – excellently performed Rob].

I’ve met lots of people who struggle with what it means to have a relationship with God, but they haven’t lost faith and love and hope and truth and compassion and justice and generosity [They haven’t lost their faith, love, hope, etc., or they haven’t lost faith in God’s love; but then is it God’s hope they haven’t lost faith in or their hope…? This is yet more syntactically correct but semantic hypnotic nonsense Rob – your audience must be fully entranced by now]. They maybe have this sense, like, you have no relationship with God because of all these ideas about what that means, all these things that you’ve been told about what it is or what it isn’t [And Rob, you think you’re helping?]. And an infinite massive invisible God, that’s hard to get our minds around [Yes it is, but you’re skipping that bit, or are they okay to continue to believe the existence of the incomprehensible? All that’s left is the song in your head that isn’t heard by anyone outside. Your own auditory cortex, your God module, is convincing you that you’re hearing things and your pushing at it, willing it to be true. And all the while you’re sort of telling the audience to forget the big God issue, though avoiding actually saying it]. But truth, love, grace, mercy, justice, mercy, compassion, the way that Jesus lived; I can see that, I can understand that, I can relate to that [So you can relate to human emotions and feelings – well done. Why the God bit?] I can play (in) that song [Don’t you mean you can hear it, in this context?]“

Okay, back to reality. Thanks Rob, that’s as clear as mud.

When we talk of mixed metaphor it’s usually that someone has tried to relay a concept using elements of two or more metaphors, so it sounds a bit silly. But this is a more obscure mixture. The metaphor is the same throughout, but it’s use changes as it appears to be applied to a relationship with an unfathomable being, as a notion for this being, for some human actions of love, or maybe sacrifice, for the misunderstanding of scripture, for what Jesus came to do, the way Jesus lived, or as a definition of God, etc. But not only that, the metaphor switches so that to be in the game you have to hear the song, or to play the song, or to play in tune with the song – and I’m not sure if it’s any of those or all.

Encountering a theist like Rob is like receiving the Chinese Whispers, where every time you pin down a point with a question the answer doesn’t quite seem to match the case being questioned; so you ask another question, and the answer has moved on to yet a different meaning – until eventually, as if by magic, the very first statement you were questioning is stated again as if it answers the last question. There you are, right back at the beginning, with nothing learned, and nothing really said. There’s no temptation to feel as if you’ve lost the debate, as if your objections have been shown to be unfounded, because you can see they haven’t; but there is a frustration that comes from knowing that no matter what you ask, the theist is locked into their own self-deception that what they are saying is actually meaningful.

So the question remains, does God exist or are we knocking Genesis on the head? Are we relinquishing the idea that this God actually exists as some entity, either ‘out there’ or in your head, or in any respect by which he is the creator God? I don’t think so, and this is where the muddle headedness comes in. Theist will say, or suggest, or imply, or sidestep, as Bell does, that it is wrong to take the creation as literal, in the sense that some powerful entity created the universe and us, and that the notion that God exists as an entity out there isn’t of concern, as if they don’t need it. But, you can guarantee that somewhere along the line Genesis will be mentioned, and in that discussion there will be no reasonable way of taking it other than literal – that God actually created the world (though they may not read it literally in the six days Adam and Eve young earth Creationism sense – there are obviously grades of literalism). In fact it’s hard to get a theist to commit to anything along these lines, which is odd, since commitment and faith are supposed to be big pluses.

Given that these ideas are developed and dispersed in the theological institutions of the church or colleges it’s not surprising that the search for a common understanding results in something that is difficult to explain for the faithful and difficult to refute for the atheist.

I’ve often asked how you tell the difference between the delusion of being Napoleon and what I see as a delusion of belief in God. Rob Bell’s explanation just seems like self-induced delusion, and I guess that’s how I see the difference between a mad man who is off in La-La land, and the theist who appears to have their madness under self-control. And because it is self-induced, under the influence of the particular religion a person holds to, it is also well controlled, with affirmations for like-minded self-inducing people.

Note I’m not saying the theists don’t believe in their God, that there is intentional underhandedness – just that the belief is so strong and so intricately supported by the church that they are incapable of willfully applying reason beyond the point where it starts to seriously challenge their faith.

Some get past this point, and become atheists – the internet has plenty of ex-theists who now pave the way for others.

And some are on the cusp – they see many of the problems with their faith, but still maintain it. They question their faith seriously and have moments of doubt. But if you suggest that they have in fact reached the point where they can let go of their faith, they are likely to backtrack and re-affirm many of the points that they have otherwise put up for questioning.

And they rely on the likes of Rob Bell to help them maintain their faith. Have I already said this is woolly thinking? Well, it’s also a psyche trick to make the audience feel left out if they say no to any of this stuff. It’s meant to draw them in, isn’t it? It’s a standard hypnosis technique. It starts off with ordinary language, slowly calmly yet still lucid, but then introduces babble that the brain can’t quite focus on and draws you into the hypnotic state – the mind, in confusion, looks for someting to hang on to. Can’t remember who said it, but, “A drowning man will clutch at a straw; so hold him under water, then offer him the straw”, but it does describe the way this video is supposed to work. Listen to a Paul McKenna CD, or get a free DIY hypnosis download, or any relaxation CD. They draw you in with babble, slowing the pace of the words, not quite enunciating them, whispering in parts to make to lose mental focus.

Look up the definition of a cult and tell me it’s different from plain old religious belief. Look of explanations for hypnosis and tell me that’s not what’s going on in Rob’s beautifully scripted video. Welcome to the world of religious language.